7.30.2007

Gun Control: Some Bullet Points

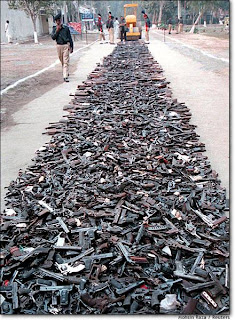

Talking about guns in the United States is a tricky thing. The Constitution is quoted by both sides of the gun control debate as a defense for either restricting the use of guns or keeping the government out of gun sale regulations. Should the government have the power to ban guns, assuming that the Constitution is too vague to be a sole authority? I don't know, but here's how I look at it.

I take as an assumption that this country is very big and that there are a few firearms laying around already. Even if we were able to pass a law restricting gun sales, disarming the public at large is definitely something the Constitution would prohibit, not to mention that it would be completely implausible. I also take as a given that, like prohibition, restriction of firearms federally would serve to expand the already quite large black market for guns so that buying across the border or from local smugglers would still be the thriving industry it already is. Moreover, while criminals would still have access to guns, the law-abiding populace would not. The notion of this puts me in an awkward position mentally.

There is the added consideration that police are not primarily designed to stop crime. There just aren't enough police officers to be around when every violent crime occurs. The foundational occupation of the police force is to respond to crime and bring the perpetrators to justice. While I'm glad that they're around, they will not be there while the actual crime is being committed, and as such it is possible for me to get assaulted or killed without police intervention. So who is charged with your defense at the time a crime is being committed? You, of course. If that is true, and (like myself) some people have a delicate constitution, shouldn't we be able to use such tools as we can (a rock, a loose brick, our hands, etc.) to fend off an individual that wants to harm us? Wouldn't a gun be a very helpful weapon in a situation like that? I'm inclined to say that yes, a gun would be helpful, and that yes, people have every right to defend themselves with the best weapons they happen to have at their disposal.

Still, philosophical musings don't appear to me to be decreasing the number of violent crimes, or the number of guns that are stolen out of homes after being obtained legally. The fact remains that people do kill people, and when they do, it's typically a gun they're using to do it. That notion also puts me in an awkward position mentally.

7.16.2007

John Ciardi and the Narrative

"My special concern is for the reader of poetry: I cannot escape a feeling that the poets must face the responsibility of providing themselves with a wider audience...if such a reader could be enlightened on what the poets are trying to do, he might come a lot closer to understanding it when he sees it done."

-John Ciardi in a letter to Karl Shapiro. April 29th, 1949.

I know that in writing this I run the risk of flogging my own dead horse. I've been yammering for over a year now that when it comes to literature, we see many of the same themes resurface again and again, and if they happen to always be in a dialectic reaction, then I leave to the post-modernists--if there are any still alive--the task of telling me yet again why oppositions are arbitrary.

The reason I keep coming back to the thesis that these romantic and 'enlightenment' ideas are seen in the history of literature throughout the course of time, always embedded in, and perhaps responsible for, the furtherance of the hermeneutic spiral is that, in hermeneutic fashion, the thesis keeps coming up. The early 1900's present to careful readers a number of modern writers hell-bent on yapping about the state of society, emphasizing stylistic flourishes, and forcing a play in language. What was the reaction? A cry for sincerity, individual transparency, and romanticism. The rise of existentialism proper, the writings of Ciardi and the forties poets, the "new" beat generation, and the general desire to tear down all pretense of modernist style all follow directly in the wake of a period that rendered some of the most difficult to understand texts in our short written history.

As we find ourselves firmly entrenched in a "post-ironic" movement, we are inhabiting the philosophical principles already seen in the 1930's. Our society doesn't want post-modern language games and spectacles. It wants to know the secrets behind the art. It wants the bridge between the author and the reader to be short and simply written. It wants language to be unambiguous and understandable.

I don't think it is an accident that right now I feel my sympathies drawn towards the ideology of the many romantic movements our textbooks record. At the same time I approach my own thoughts with an amount of hesitation equal to my eagerness. If we are just going through this cycle all over again, and we know it, isn't there a way to start in a new direction? Is there something outside of individual sap-stories and the cryptic style-sessions of the language movements? Is there something between people and the society they live in, some other area philosophically unexplored, passed over as we fluctuate between two extremes and ultimately re-pen the same things? Something tells me there just might be. I just don't know if we'll ever find it.

7.09.2007

Buried Alive

Remember all the times we tried to bury the word Stupid?

Remember all the times we tried to bury the word Stupid?The NAACP decided in April that today would be a monumental day. Meeting together for their annual summit, the traditional leaders of the Colored People's Movement came to the conclusion that today they would bury the N-Word. This is a big step for them. Nay, it's a big step for all of us.

The idea that a group can put to rest a word, something that is completely abstract, something that rarely exists in the tangible world, is (for language junkies like me) kind of a deal. I mean, how does one go about that? How does one accumulate such an overpowering influence over the meta-narrative itself that you can banish words by holding, of all things, a literal funeral. NAACP delegates carried a casket behind them with fake black flowers over the top of it. A symbolic gesture to kill a signifier, or at least to bellow to the world that the signifier could no longer be used to point to the sign it was originally intended for. Surely, my friends, we've left the age of post-modernism when something like this would be mocked and dismissed by all.

Hermeneutically, of course, they could never kill the N-Word. The trace goes on, and even talking about it as you put it in the ground reinforces the truth that the word is far more powerful than any mortal speech act. Still, its true that for more than half a century the word has come to greater and greater disfavor as it becomes less socially acceptable. So how does one effectively imprison a word? Influence the society that depends very heavily on the political power of language. It's true that as a nation we've become a little timid in our social gestures, more aware of how we are discussed by the world-at-large, more concerned with how much capital a good reputation equates to. We've become enslaved to the global dollar, and every person willing to give us one has feelings that we probably shouldn't hurt. A mentality like that very easily could lead to a truly political citizenry. That is to say, all smiles in public and backstabbers in the dark. I think we're getting to that point.

The last time the NAACP had a funeral like this, it was the symbolic laying to rest of Jim Crow in 1944. Isn't it funny how the first was a symptom of the rise of existentialism, and this one comes on the very heels of the so-called "post-ironic" movement? It's enough to make a person think that there are circles in our social history. It's enough to make that person think that you can trace them back all the way to Greece, trace them like veins in a hand following all the way back to a pulsing ideology that passes the cultural and the individual considerations back and forth through its beating filter, passing them out only to call them back. It's enough to make a person believe that the currency through which we find the base of our civilization is teeming with the overlapping history of words, the timelines of how and when they were born, that somehow those movements in our philosophical history are always a signifier for the sign of the language we use to express them. We do not note the death of a word. We do not notice the death of a word. That's what makes it dead. I doubt we will ever become so self-conscious that we, as a society, manically trace all our hermeneutic roots to find out what ideas we lost when we lost the words to express them. I think it is enough to note that the N-Word has not yet passed, try as we might. I hope that means we're still working on the problem that brought it into use in the first place.

7.05.2007

Our Arctic Ally, the Nanook

Two patriots keep us safe for about the seventieth time this year.

Two patriots keep us safe for about the seventieth time this year.Outside of their historic significance, polar bears are also the number one killer of seals. Terrorizing fish schools, capsizing oil tankers, and causing glaciers to fall into the sea with their bellowing roars, seals are dangerous and unnecessary beasts who care only for themselves. While Inuits traditionally cowered and paid tribute to the Tyrants of the North, polar bears held the Great Arctic Convention of 1775 in which they decided to declare war on the seal nations and bring them to justice. With sharp claws and their natural camouflage, polar bears have been responsible for the deaths of more than one million seals, and they are proud to tell all curious tourists that they are still counting.

This noble bear has a keen sense of smell that allows it to sniff food ten miles away upwind, and more than twenty downwind. Though the polar bears can't run because their bodies are highly sensitive to fluctuations in temperature, polar bears have the unique ability to sleep while they walk; as they get within a certain distance of their prey, they awake fully refreshed and thirsty for equality. Polar bears are also one of the only bear species that does not hibernate during the winter. This allows them to protect our oceans year-round from both the threat of the ice and that of the seals.

While there are many in the media who attack polar bears, wanting us to believe that they are soft on crime and undetermined to break us from our dependence on foreign oil, there is little evidence that this is anything more than a political ploy, a plot for panicked politicians to score an easy point using fear. Polar bears continue to be the number two supporter of alternative energy sources (after this guy), even if they remain adamantly opposed to the expansion of Alaskan drilling into ANWR. Drilling these wildlife reserves will destabilize the region, allowing a refuge for cunning and dangerous seals to conceal themselves in oil and make their way down into the United States. Because of their dedication to national security despite their mounting political unpopularity (and lack of citizenship), it is unreasonable and cruel to try to label polar bears soft on crime. If we continue to belittle our allies in the War on Seals while we slowly give way to the sentiments of liberal seal-friendly environmental groups that have no regard for the damage they do to polar bear morale, then we may find ourselves in a very deep and icy spot. Believe me when I tell you that those are the places seals like most.

7.02.2007

Serial Literature, Fiction's Lost Genre

Novels command a certain amount of respect.

Novels command a certain amount of respect.The premise has become the foundation for our television shows, our kids books, and our news cycles; the genre encompasses some of the most well-known writers of the last century, from Ernest Hemingway to Rudyard Kipling (and, if fact, it secretly got Kipling a Nobel Prize). It never has caught on here in the states (and I can almost guarantee it never will now), probably because those who practiced it best were almost always British. And yet, one of my favorite genres in the history of literature is also one of the most ignored today. Of course, I'm talking about serial fiction.

The idea of writing multiple stories about one character (or group of characters) first became famous in the late 1800's, specifically with the publications of A Study in Scarlet (1887) and The Jungle Book (1894). Though there were people who did it before, the wide dissemination and instant popularity of Sherlock Holmes and Mowgli (respectively) left a strong impression. To me, the idea still does.

Similar to a novel, someone who writes bunches of stories can develop and flush out characters while tangling with some overarching themes. Unlike the novel, the authors are not tied to one plot-line, and since the stories are shorter than a typical novel chapter, they can write more in less time, thereby retaining an audience more effectively. There are other advantages, too. Since each story stands alone, they are typically more compelling and less long-winded. Since the authors aren't going through a publishing house, the deadlines are almost non-existent.

So why has serial fiction fallen to the likes of Encyclopedia Brown and The Hardy Boys? Partly, I think, because kid's books are the only things that sell when they are short and skinny. Moreover, publishing companies run this country like a 1960's numbers racket, and ten thousand over-hyped novels are cheaper to manufacture than ten thousand well-constructed copies of a magazine. Some of it, I'm sure, also has to do with literary magazines not even having half the readership of a rural newspaper. The most critical factor, beyond all others I'm positive, is that magazines don't pay for stories anymore, and authors get royalties for novels. The combination of all those things is pretty damning.

Still, I would like to see someone try and bring it back. If J.K. Rowling, on her Harry Potter victory lap, announced that her next project would be an epic released in subsections to a variety of different literary magazines (very similar to how James Joyce published Ulysses, by the way), she could no doubt revolutionize the industry. Besides taking money out of the hands of the large publishing blocs and giving it back to the places that have always pushed the medium forward, she could also encourage multiple generations to read more than one book every two years or so. Serial fiction was more popular than novels when Kipling and Doyle were done, and I think it could happen again if the right person were to give it a kick start. Perhaps I'll write J.K. a strongly-worded letter about it. Perhaps you should too.

6.28.2007

Habeas Corpus: An Old Law and a Strange Situation

Paris Hilton revels in her legal rights.

Paris Hilton revels in her legal rights.On June 26th I had the distinct pleasure of joining some of our nation's Congresspersons as they discussed habeas corpus, and more specifically whether it applies to those people who are being held in Guantanamo Bay as enemy combatants. Before I introduce the battle, let's have a brief look at those people who we'll be talking about.

Rep. Nadler, Chairman, Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties

Rep. Franks, Ranking Minority Member

Mr. Katsas, Department of Justice

Lt. Com. Swift, Office of Military Commissions

Mr. Taft, Attorney

Mr. Berenson, Former Associate Council to the President

Mr. Hafetz, New York University School of Law

There were some other minor characters like Rep. Ellison and Rep. Jordan, but in the gloss these guys are the ones really throwing around the language. The whole thing starts with Mr. Nadler scolding some Code Pink ladies who showed up. He reminds them that this is a serious debate for serious people and that they shouldn't yell at the Congresspeople present. This because only a couple of days earlier Code Pink actually did have some screamers and they had to be booted out of a hearing by local law enforcement. He then reads an incendiary opening statement in which he whips out Federalist 81 and sprays it all over the composed face of Mr. Franks. He chats about tyrannical power and how there needs to be some sort of oversight in Guantanamo. His main beef? President Bush and the office of the Executive gets to chuck people into our prison in Cuba without telling anyone who's down there, what for, or for how long. This could result in a "disappearing person" incident in which a person is abducted by us and is never seen again by human eyes, most specifically those of his family. These situations tend to be unsightly (pun), and cause some turmoil. He then yields to Mr. Franks.

Mr. Franks, cool and composed, gossips to the room about how the Constitution doesn't guarantee habeas to anyone (true), much less foreigners. He says that people in Guantanamo are "bloodthirsty killers," and that the "liberal intelligentsia" has some really "insane notions." Mr. Nadler appears undisturbed, but ready to strike. It's time for the five witnesses. There are five minutes from each person, but I'll save you the trouble since the question was pretty simple.

Do you think that we should allow persons in Guantanamo Bay to petition for habeas corpus?

Katsas: no-we already give them too many protections

Swift: yes-remember that one time that we signed at the Geneva Convention?

Taft: sure-we could use a dose of credibility and we're a little lacking

Berenson: no-these people are crazy

Hafetz: yes-Berenson is crazy

Pretty intense, and an even divide. Mr. Nadler decides to take on the biggest fish first. He swivels to Berenson and lines up for the kill. He asks Berenson a demure question-"What provision is in the law right now that requires us to make sure we have the correct prisoner and a reasonable cause to hold them without trial?" "A Combatant Status Review Tribunal," he responds. "We aren't legally obligated to do that, though, are we Mr. Berenson?" "Well, no, but it's the Administration's policy..." Mr. Nadler then gives a very scandalous rant about the policies of the current Administration, makes CSRTs sound like a bunch of monkeys jerking off around a fire, and then asks again what the LEGAL obligation is to prove that we are torturing the correct person in Cuba after ripping them away from their homeland. Mr. Berenson goes quietly to sleep and dreams of a place where angry people don't yell at him.

In defense of Berenson, Mr. Franks lets loose that Jihadists are Nazis and that only bounders and scoundrels talk about legalities when fighting terrorists. He lays into Mr. Taft and comes up with a foul ball. Mr. Taft, you see, is no ordinary man. He's actually William H. Taft IV of the Taft Presidency seed, and his house will not fall to the likes of a mere Arizona Ranking Member. He specifically addresses that he doesn't think we have to give Guantanamo prisoners habeas corpus, but that the court already knows how to handle these proceedings and the cases will be straight-forward since most of the people held there (of the 375) are either leaving soon or openly admit that they will attack us if set free. Mr. Taft thinks we're only talking about a handful of cases that call for due process and those should be addressed as good global politics. Mr. Franks is stunned into silence by the eloquent solution this man has put forward, and Mr. Taft is never called upon again by either party.

Mr. Nadler then calls on Swift to patronize to Mr. Franks, and Mr. Franks calls upon Mr. Berenson to condescend to Mr. Nadler. After about four hours of bickering, they end the hearing with nothing decided, though Mr. Nadler clearly has the more powerful tongue and Mr. Franks appears full of gas.

But what's the real deal? Actually Mr. Taft (IV!) brilliantly put forward the exact problem and solution. At a time like this when we have no other legal recourse, of course we have to give people the ability to contest whether or not they actually are enemy combatants. That most of them freely say yes they are makes the process that much more simple. Unfortunately, I know exactly why Mr. Franks and the other Republicans really really resent this solution. Over the course of the hearing it became obvious that Mr. Franks really does believe that Liberals are willing to do anything to help terrorists, and that they do so intentionally. Even though the Supreme Court has a conservative majority right now, most appellate courts are still liberal-leaning. The thought of trusting the sensitive cases of terrorists to a liberal court that will release them on a technicality while knowing full well that they are our enemies seems to them like horrific policy and bad public service. At best it hands liberal judges cases that they can use to say that they are tough on crime, and at worst it leaves Republicans in a position where they have to justify to the American people why a known terrorist has just been set free.

But then again, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of extending habeas corpus to Guantanamo detainees before, and even Republicans don't entirely trust the President to have the only say in who goes to jail and for how long. I mean c'mon. What if we get a Democrat President?

6.25.2007

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Art of Reduction

An average United States citizen learns how to swim.

An average United States citizen learns how to swim.Right now I'm slowly making my way through The Complete Sherlock Holmes. I say slow because I read about as fast as slow-to-mid-level student of the third grade, and if that isn't enough of a hindrance, the object itself is a pretty impressive tome of somewhere around 1100 pages. Still, even a person as dense as myself is forced to pause for a second.

"There's something going on here," I muse to myself, "that reads a little funny."

Some further thoughts occur. In Doyles' stories, Sherlock Holmes is a very shrewd mind capable of deducing a number of things because he treats his mind like an attic. As he states,

"you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things, so that he has a difficulty in laying has hands upon it."A novel thought, and one that becomes a theme in Doyle's stories.

His epistemology, extracted from various comments and plot lines, must read something like this: There are too many things in the world to know, so many in fact that it would be impossible to learn even a fraction of them, so the person who is truly wise will pick one specialty and will have no concern for anything else. In true late-enlightenment fashion, these specialties are not always bound by traditional disciplines. Holmes has perfected the art of solving crimes, and even the word perfected might be an understatement. In order to do so, he had to take relevant data from Botany, Geology, Chemistry, Anatomy, and a number of other traditional fields, but as a student in any of them, Watson tells us, he would be limited at best.

Many other characters become the victims of depending too much on one discipline. Lestrade, a Scotland Yard detective who is energetic and good at the physical task of gathering evidence, sometimes doesn't know what he's looking at once he's got it. Many of the criminals have studied some profession or another, but end up getting caught because they have no consideration for the art of crime. And that is exactly how Doyle thinks of it, as an art-form.

Professor Moriarty, Holmes' arch-villian, is not psychologically disturbed, did not come from a bad home, and is a functioning member of society. He turns to crime because, as he studied the field the exact same way Holmes did, he found that he would rather use his knowledge to his own advantage and not for the aid of others. There is no indication that he is less knowledgeable than Sherlock Holmes, and that is what makes him the most dangerous.

So what makes an average guy like me hesitate? Well, outside of the fact that in the US criminals are archetypically shown as being somehow motivated to crime by psychological problems, fits of rage, or mere stupidity (perhaps a mixture of the three), and rarely have any claim to knowledge, our standard detective is a bit of a cad. On CSI our detectives can be seen labouring over a case for twelve hours a day, studying all the evidence, cataloging the minutia, memorizing it, taking everything into account before finding the deranged person who was not operating rationally at the time. Epistemologically, that says something rather backwards in our view of humanity, perhaps something like this: In order to gain knowledge, you must study hard, follow the methods you were taught in school, and work really long hours (or else you're just some crazy and being a crazy means you're also probably a criminal).

Considering that Holmes very rarely has a case he does not solve in three days or less, a side-by-side comparison says something about our method of attaining success. In our view, if you go through the process that you've been taught, you will succeed. In Doyle's view, it takes more than bookwork (and more than an adversary, really) to succeed, it takes an intentional narrowing of one's focus and a concerted effort to clean out all other things over a lifetime. It also takes the imagination to see a new study between the established fields that are taught to everyone else.

The difference in ideology is noticeable in reality, and I have to say I'm a little worried. Our typical media impressions appear to reinforce the institutions of education that are becoming rapidly outdated, and telling kids to study hard isn't enough anymore to ensure their success. Further, we appear to be telling people that you don't necessarily have to be smart to hold a job, you just have to be willing to work a lot of hours, and if that is true, our corporations are going to hit some major road-blocks when all they have left are automatons in their leadership roles. Thinking between established fields to find new technologies, new methods, and new ideas are what has made the United States the economic force that it is. Teaching kids that they have to develop a creative mind and apply that creativity to their studies, not just get good grades, and that they have to take charge of their own education, puts more responsibility on their shoulders and forces them to learn. Instead of teaching our society at large that they only need to sit back and take notes, I would rather teach them, as Holmes teaches Watson, that in order to succeed, "you need a little imagination." Does that notion read a little funny?

6.21.2007

The Sanctity Of Life

Rabbits don't lay eggs.

Rabbits don't lay eggs.In the beginning was the proclamation "whosoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed..." (Gen 9:6) and in the end there was "Father forgive them, they know not what they do" (Luke 23:34). In between is a complex problem left completely unresolved, and too many verses for even the scholar to sift through authoritatively.

The question: Do we have the justification to kill? Capital punishment still exists in Christian societies, and most look to the Law set out by God in the Old Testament. After all, the Old Testament and the New Testament are divided so that the Old Testament deals with societal ethics, and the New with personal ethics. Therefore, though Jesus said to forgive personal offences, the Law and the judges are compelled to destroy those who insult God. Hank Hanegraaff articulates the argument for capital punishment best when he says that it is a "sanctity of life" issue. Those who kill the apex of God's creative energies are not only destroying a human being, they are sending a personal defiance to God, a personal attack against His sacredness. To allow such a rejection of God's Will is to reject God's majesty and a court cannot do that. Such people need to be terminated, if only because an insult to God should not go unpunished.

But there are those who do not agree. The charges brought against Jesus by the Sanhedrin, those that ultimately led to his crucifixion, were of rousing the Jews not just against the Romans, but against God (Mark 14:60-65). The Law passed down from Genesis to punish those who insult God with death was the same justification used to kill his Son on a cross. If one who is without sin can slip through the Law, then there are others too. Those on the other side say that the Law was replaced, through Jesus' subjection to it, by Love and forgiveness.

Still there is no way to know for sure. Jesus did not come to change the government; he specifically tells Satan that when he is tempted in the desert. If that is true, then perhaps the Law still stands and the sanctity of life must still be defended. To the death.

6.18.2007

Salman Rushdie and the Sea of Stories

Another day, another mixed bag of death threats and honors for Salman Rushdie. Sorry--Sir Salman Rushdie. Knighted by the Queen of England for, presumably, his expansive tomes based not-so-loosely off The Arabian Nights, Rushdie had not even exited the building when riots broke out in Pakistan. The lower house of the Pakistani government, pushed to arbitrary action by protests in the street, shot off a condemnation that passed unanimously through their ranks.

For those unfamiliar with the scandal and gossip, Rushdie penned The Satanic Verses with a section that explores the life of the Messenger Mohammed. Based on the original "Satanic Verses," but with a couple details added, Rushdie posits that Mohammed originally called for polytheism to become popular and that his scribe changed part of The Qur'an because he wasn't sure if the Messenger was correct. This in a culture that refuses to create any sort of artistic imagery, however lovingly rendered, of the Prophet or God because the art of mortal hands is lowly to the sacredness God. A man who breaks this age-old tradition of worship to, of all things, profane the name of the Prophet could certainly be seen as quite the sensation.

I guarantee a stoner somewhere is perking an eyebrow between thoughts of how totally connected everything is, and is now telling his friends that he is psychic. "Like, a really long time ago," he opines, "I totally saw this happening on TV or something, but it was like in my head and I like saw the future, dude. I'm telling you, man, it's all the same and it's like totally in my head!" That stoner is only partially wrong. It wasn't in his head and he didn't see the future, but he is witnessing the past all over again. In 1989 riots broke out in Islamabad over Rushdie's The Satanic Verses, and Ayatollah Komeini called for Rushdie's assassination.

That same stoner also has a point. It is interconnected. The Arabian Nights, The Qur'an, and the "Satanic Verses" are very old documents with very long histories of influence. As a member of a huge number of modern and post-modern writers who dug through the collective past of their people to bring rebirth to texts long out of common reading, Rushdie did to these books what Joyce, Bulgakov, and Derrida did to Homer, Jesus, and Plato. But it wasn't just about that, was it? Was there something else they had in mind? Oh, right! The hermeneutic legacy of books themselves! These texts are constantly being reinterpreted, retranslated, reconsidered, and reworked. They are the bedrock of creativity and as such they have no choice but to breathe through change. The intentional choice to reinscribe one of these relics is supposed to draw attention to the unintentional reinterpretation that happens in the heads of avid believers all the time. The conception that we have of Jesus isn't the same as the one carried in the Middle Ages. For that matter, neither is our conception of Plato. And it shouldn't be. The more we learn about the context and the language, and the more we think about these books, the more we contemplate our own situations, expressions, and very existence. In other words, the more we critically analyze these great tomes, the more creative we become ourselves.

Islam never quite learned to deal with post-modernism the way the so-called "Western Tradition" did. The people are furious, and they shout, and they try to put Rushdie to death, and they generally make quite the spectacle of themselves. The United States found a better way to kill their creative authors. Ignore them.

For those unfamiliar with the scandal and gossip, Rushdie penned The Satanic Verses with a section that explores the life of the Messenger Mohammed. Based on the original "Satanic Verses," but with a couple details added, Rushdie posits that Mohammed originally called for polytheism to become popular and that his scribe changed part of The Qur'an because he wasn't sure if the Messenger was correct. This in a culture that refuses to create any sort of artistic imagery, however lovingly rendered, of the Prophet or God because the art of mortal hands is lowly to the sacredness God. A man who breaks this age-old tradition of worship to, of all things, profane the name of the Prophet could certainly be seen as quite the sensation.

I guarantee a stoner somewhere is perking an eyebrow between thoughts of how totally connected everything is, and is now telling his friends that he is psychic. "Like, a really long time ago," he opines, "I totally saw this happening on TV or something, but it was like in my head and I like saw the future, dude. I'm telling you, man, it's all the same and it's like totally in my head!" That stoner is only partially wrong. It wasn't in his head and he didn't see the future, but he is witnessing the past all over again. In 1989 riots broke out in Islamabad over Rushdie's The Satanic Verses, and Ayatollah Komeini called for Rushdie's assassination.

That same stoner also has a point. It is interconnected. The Arabian Nights, The Qur'an, and the "Satanic Verses" are very old documents with very long histories of influence. As a member of a huge number of modern and post-modern writers who dug through the collective past of their people to bring rebirth to texts long out of common reading, Rushdie did to these books what Joyce, Bulgakov, and Derrida did to Homer, Jesus, and Plato. But it wasn't just about that, was it? Was there something else they had in mind? Oh, right! The hermeneutic legacy of books themselves! These texts are constantly being reinterpreted, retranslated, reconsidered, and reworked. They are the bedrock of creativity and as such they have no choice but to breathe through change. The intentional choice to reinscribe one of these relics is supposed to draw attention to the unintentional reinterpretation that happens in the heads of avid believers all the time. The conception that we have of Jesus isn't the same as the one carried in the Middle Ages. For that matter, neither is our conception of Plato. And it shouldn't be. The more we learn about the context and the language, and the more we think about these books, the more we contemplate our own situations, expressions, and very existence. In other words, the more we critically analyze these great tomes, the more creative we become ourselves.

Islam never quite learned to deal with post-modernism the way the so-called "Western Tradition" did. The people are furious, and they shout, and they try to put Rushdie to death, and they generally make quite the spectacle of themselves. The United States found a better way to kill their creative authors. Ignore them.

6.10.2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)